Cabaniss chronicled

May 9, 2024

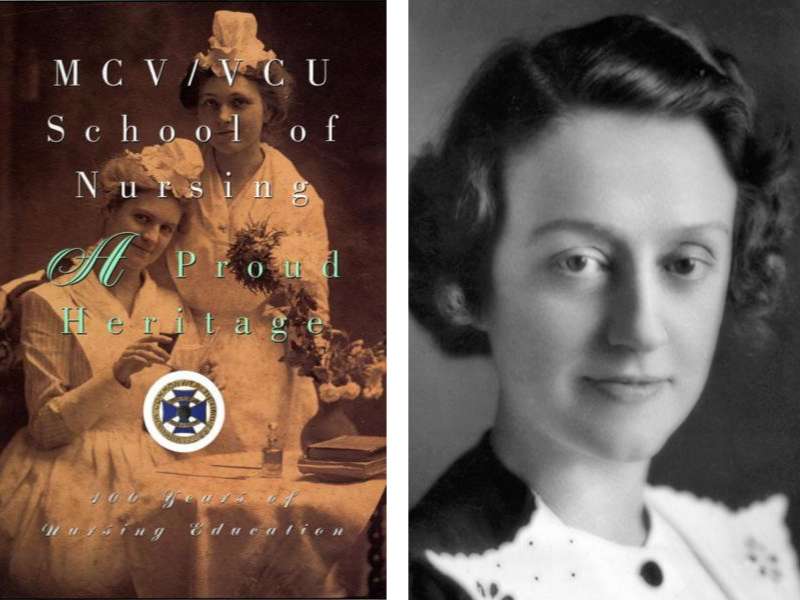

The history of the VCU School of Nursing is well documented courtesy of alumna and professor emerita Betsy A. Bampton (BS '60/N, Cert '80/N) who authored the publication “MCV/VCU School of Nursing: A Proud Heritage.” The abundantly illustrated history was published in 1992 to mark the school’s centennial year. Within the pages of the book are some hidden gems—startling, little-known or long-forgotten revelations about student life, faculty personalities and the campus environment.

Read on to discover some of those stories or visit a full text version of the book available for download courtesy of VCU Libraries.

MCV/VCU School of Nursing: A Proud Heritage

The class of 1930 staged a rebellion during their freshman year. The student nurses were highly insulted when the ladies auxiliary of the Richmond Academy of Medicine sponsored a freshman reception in the dormitory so that the medical students could meet the ‘nice girls’ of Richmond. The nursing students were instructed not to be seen on the first floor. A newspaper article stated that, ‘The rebellious young women raided the ice cream supply, sewed up the sleeves of most of the clothing left in the check room [and] stole away the escorts of many of the guests.

Prior to 1928 when old Cabaniss Hall dormitory was opened, living quarters left much to be desired. The students attending the Virginia Hospital Training School lived on the upper floor of Virginia Hospital, and they called it the ‘nurses flats.' Dorm life was far from comfortable. Sleeping quarters were crowded and bathing facilities were most inadequate. Hot water was available on Saturday only, and on other occasions it was obtained by placing a pan of water over a heating grate.

Smoking was prohibited until 1929 when the dean sent a letter home to parents describing the problem of student smoking and asked for parents' views on the subject. The letter stated that the ruling of no smoking no longer prevailed in the school because of its repeated violations. The students had been told that the faculty disapproved of their smoking, and they had been asked to refrain during the three years they were in training; but smoking was on the increase. Whether the letter home made any difference is not known. Students continued to smoke even though it was prohibited in the dorm rooms.

Students at Old Dominion Training School [1895-1903] lived in a house next to Monumental Church. The physical comforts were not much improved, and it was across the street from some of Richmond's toughest saloons and the red light district. Three students shared a small room, there were no screens on the windows and bugs invaded the living space. The students attending Memorial Hospital Training School also lived there. Eventually this house was razed to build Cabaniss Hall. Living conditions were so deplorable at the time that enrollment had dropped.

The influence of Miss [Lulu K.] Wolf [a faculty member of the school from 1930-1938] was exactly what MCV needed. She described herself as a ‘chronic irritant’ during her student days because she rebelled at the notion of simply following rituals. This spirit of finding new ways to do things was a part of her fabric. She was an advocate of the students' right to be students and concentrate on learning without being responsible for staffing the hospitals. While at MCV, Miss Wolf became convinced that public health nursing should be an integral part of basic nursing programs. She even challenged racial segregation by combining the students in St. Philip and MCV Schools of Nursing for lectures. In this way both student groups not only had diplomas but they had certificates and were called public health nurses.

A tunnel connected Cabaniss Hall to the capitol and the various hospitals on the MCV Campus. Students also found the tunnel useful for unauthorized entrances and exits. The cafeteria in the basement of Cabaniss was a welcome change. Previously the students had eaten all their meals in the hospital. One student commented that it was not unusual to pass rats on the stairs leading to the cafeteria in Memorial Hospital.

Student’s whereabouts were closely monitored. It was necessary to sign in and out at the housemother's desk. The hours a student could be out of the dormitory were restricted. It was not proper for students to walk on the north side of Broad Street, opposite the old City Hall and Thalhimers, because it was adjacent to the ‘bad section’ of Richmond. Students had to receive special permission from parents for weekends and late nights. Faculty who lived in the dormitory would often check the sign-out sheet to see who was out.

Students had to keep their hair long and pinned up until around 1926 when short hair was permitted, but a net had to be worn on duty. The uniform could be worn only in the hospital and dormitory. When a student left the dormitory, she had to be in a dress with hat, gloves and pocketbook.