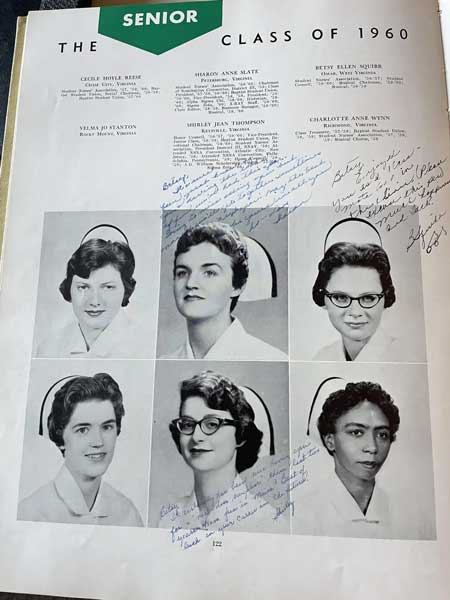

With poise and grace, VCU’s first Black nursing graduate charted a path – and even schooled the faculty on a memorable day

February 22, 2024

Deep in the archives of James Branch Cabell Library, two documents – one a blurry carbon-copy from 1965, the other a journal article from two years later – manage to both give voice to and disguise Charlotte Anne Wynn Pollard.

In a folder labeled “Desegregation and Nursing Schools,” the documents are part of the archived papers of Edward H. Peeples Jr., a former Virginia Commonwealth University faculty member and civil rights activist. And they hint at both progress and peril along the ongoing path toward equality.

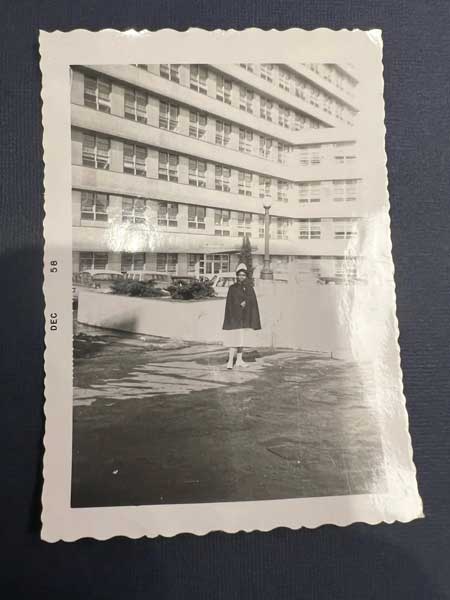

The first document, 23 pages on yellow paper, transcribes a 1965 event. Titled “Intergroup Relations in the Academic Setting,” the gathering centered on an interview with Pollard – the first Black nursing student at the Medical College of Virginia, a precursor to VCU. Pollard was an MCV student from 1957 to 1960, and at this faculty event five years later, Gloria Francis, a professor of psychiatric nursing at MCV’s School of Nursing, directed a question-and-answer session in which Pollard calmly responded to two dozen inquiries about her experiences.

I was just going to school. I never thought about the fact that this was integration. I just want to be a nurse, and this was the school nearest to me.

Charlotte Anne Wynn Pollard

The second document is a copy of a June 1967 article from the journal Nursing Outlook. Titled “A Minority of One” and authored by Francis, the article reworks and distills the Pollard interview transcript – but names neither MCV nor the individuals from the event two years earlier.

In the journal’s table of contents, a summary of the article uses terminology of the era and asks: “How does it feel to be the only Negro student in a southern school of nursing?” It then explains how nursing faculty, in preparing for more Black students joining the program, attended the interview as part of their training. The summary concludes: “The results were illuminating.”

They were – and still are.

In a 2019 recorded interview, Peeples, who died later that year, said the journal article became an impactful model for nursing schools across the South at the time. He said MCV nursing faculty had organized the 1965 event to shine a light on the racism Pollard faced, so that instructors could develop more empathy and improve the setting for two incoming Black nursing students the following school year.

In his book “Scalawag: A White Southerner’s Journey through Segregation to Human Rights Activism,” Peeples recalled that the MCV administration in the mid-1960s, amid its resistance to integration and frank talks about racial discrimination, did not want the nursing faculty to hold the event or publish the article. But Peeples wrote that the session would highlight Pollard, a Richmond native, in human terms: “As a person she was condemned to obtain her nursing education in a cold and hostile environment.”

'There were painful situations'

In 1965, Pollard was just a few years out in the world with her nursing degree, working in the hospital where she studied. She had recently married a pastor at Mt. Nebo Baptist Church, and they had a 1-year-old son. At the interview event for faculty, Pollard remained poised at she fielded questions such as, “What kind of responses from the rest of us helped you feel more comfortable and more accepted as an individual [or] made you very uncomfortable, unaccepted and rejected?”

Pollard’s responses remain searing today. She noted that when she entered the MCV School of Nursing in 1957, classmates often refused to speak to her outside of class.

“People would move away physically,” she said. “Though there were painful situations, they were clear indications as to where I stood.”

Support from family in Richmond helped Pollard endure slights that included not being welcome in the MCV cafeteria.

“I had been eating there for maybe a week or two and, in going through the line, two of the nurses said, ‘You don’t belong here,’ and I was quite surprised. I looked around and I said, ‘Well, I am a student in the baccalaureate program at the medical college.’ One of the nurses said, ‘Well, I’m sorry, you don’t belong,’ and pointed toward St. Philip’s cafeteria,” Pollard said, citing the segregated nursing school MCV had established to serve Richmond’s Black community from 1920 to 1962. “I tried to be as polite as I could, and at the end of the summer, I was called in and told that I would no longer be able to eat there.”

Pollard had to eat and live with St. Philip students, and she lamented the disconnect the situation created among her MCV classmates: “When I came back from the summer, we would leave class and we would have to separate to go to eat and then we would have to join together again.”

And as Pollard was navigating both a challenging course load and a social minefield, she faced moments of self-doubt that belied what she knew intellectually – a perspective she shared with the assembled faculty.

“I know in reality that this was not my personal deficiency but again a part of our society. This is a constant reminder of ‘difference’ and a suppressed feeling of not being acceptable that one has even knowing the reality of a society, so this again is a blow at self-esteem and self-confidence,” she said. “Maybe I can summarize this by saying, physical separation and social restrictions require more effort on the part of both groups to get to know each other, so they furnish a sort of barrier to forming natural friendships.”

Pollard described having stronger ties to her classmates during clinical work, outside of the social restrictions around campus, as the nursing students could bond through shared challenges. Indeed, that was part of her educational goal.

“I was just going to school,” she said, summarizing her mission at MCV. “I never thought about the fact that this was integration. I just want to be a nurse, and this was the school nearest to me.”

In his book, Peeples wrote that Pollard’s vivid recounting of the inconvenience, insults and isolation she endured en route to her nursing degree “visibly moved” the faculty attending the event – including some who resisted integration.

Through a family’s lens

In the same folder as the two archival documents, a copy of Pollard’s undated résumé shows she went by the name Anne. She was born and raised in Richmond, and she studied at Wheaton College in Massachusetts and Virginia Union University in Richmond before joining the MCV School of Nursing program.

For Pollard’s descendants, the transcript of the 1965 faculty event gives them new insight into her experiences. Her son and daughter-in-law describe Pollard as smart, brave, calm, warm, community-focused, caring – and ahead of her time.

Donald Pollard Jr., a Comcast Business senior sales manager based in Atlanta, reflected on his mother’s challenge, in 1965, of having to speak clearly but carefully.

“Here’s a woman who is absolutely being asked what she’s had to endure and go through, but had the courage, the humility, the grace and the intellect to be able to answer all the questions and not even be in a ‘gotcha’ or even come across as being angry, but seeking to provide wisdom, guidance and positivity,” he said of his mother. “If you read that and you look at that and you hear that, that is 100% who she is and who she was.”

“She was really smart. She would have been a doctor had she not been a woman and Black,” said Pollard’s daughter-in-law Nicolle Parsons-Pollard, Ph.D., who earned three degrees at VCU and is now provost and executive vice president for academic affairs at Georgia State University. “I think about the barriers that someone like her had. That’s one of them. And had it been a little later, she probably would have achieved those goals.”

Parsons-Pollard said her mother-in-law told her about the lonely experience of nursing school, with no white students befriending her – which struck Parsons-Pollard as particularly sad, because “as a young person going to school, it is oftentimes some of the friendships that you have for the rest of your life.”

But even returning to the dorms at St. Philip presented a challenge for Pollard.

“The Black students felt like she thought she was better than they were because she spent all day with the white students in a different classroom kind of environment,” said Parsons-Pollard, who has studied her mother-in-law’s extensive journals. “She said no one quite knew how hard that was and how lonely she did actually feel – because, as you might imagine, you get back to the dorm and they would talk about and engage over things that had happened during the day. And she hadn’t been there. And they weren’t the people she’d spent her days with.”

Donald Jr. said his mother did not dwell on the challenge of integrating the MCV School of Nursing. She had more of an attitude of “what’s ahead of me?” instead of “what was behind me?”

I pray history will remember her and those like her with the honor, dignity and respect they deserve. It’s relevant to me because there are people in the world who would have us forget that segregation existed and that it was harmful – not only to those marginalized but to the majority population as well.

Nicolle Parsons-Pollard, Ph.D.

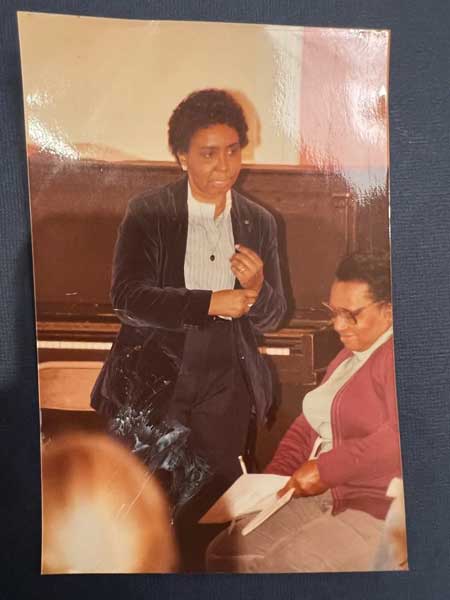

And what was ahead was an impressive set of achievements. When Pollard spoke at the 1965 faculty event, she was an in-service education director for nonprofessional staff at MCV. According to her résumé, she began teaching in the Virginia Community College System’s nursing programs in 1967 and was active in nursing sororities. She also started a business called Health Unlimited, through which she gave presentations on stress management, holistic health and other topics.

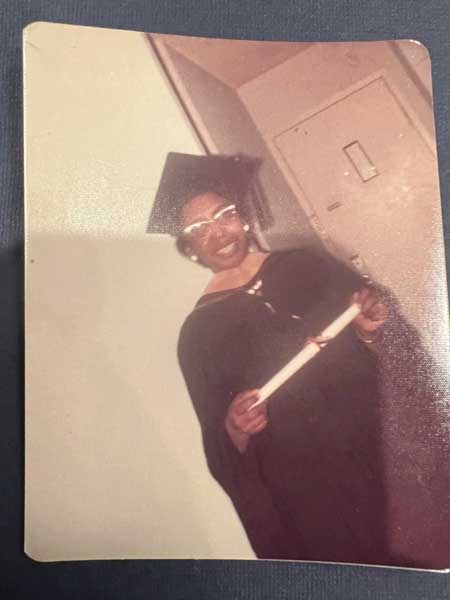

Pollard earned her master’s degree in psychiatric nursing at the University of Maryland and pursued a Ph.D. at VCU, which was formed in 1968 by the merger of MCV and the Richmond Professional Institute. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, she worked as a registered nurse with psychiatric patients and helped write and teach the psychiatric rotation curriculum as a nursing instructor at what were then John Tyler and J. Sargeant Reynolds community colleges. She also worked part time for Charter Westbrook psychiatric hospital for 10 years and, through its speakers bureau, delivered many talks on self-care for caregivers.

In addition, Pollard worked in home health care for psychiatric patients and worked for the state of Virginia. She further served as a parish nurse and was a deaconess, organist, Sunday School pianist and senior choir member at First African Baptist Church.

Committed to community and empathy

Faith and family were, and still are, key themes of Pollard’s story. She had a strong mother who propelled her daughter’s education, Donald Jr. said. Her father worked as a janitor at MCV, making his daughter’s achievements there especially powerful.

Donald Jr. said his mother’s interest in psychology was linked in part to wanting to understand racism better – as well as to serving a larger need.

“The other piece of it was, ‘Where does my community need the most help?’” he said. “Nobody’s talking about mental health. It was taboo back then. Our community was not going to seek out treatment for mental health illness. My mom would seek to take the stigma away from that,” including through her focus on holistic health and supporting caregivers.

For Pollard’s two grandchildren – Donald III is legislative director for U.S. Rep. Jennifer McClellan of Virginia, and Alexandria is an attorney in Chicago – the transcript from 1965 offers insight into who Pollard was as a young professional, much as they are now. They admire the resolve of a grandmother who died early in their lives.

“She stayed true to herself the entire time, her entire life,” Donald III said. “She had a sense of self-awareness of her being the first, her sense of self and her place at the school. And I kind of see her as in limbo because she wasn’t at St. Phillip – she was at MCV but made to feel ‘less-than’ in certain instances.”

“It’s really nice to see where she was at in this mindset at this age,” said Alexandria, who took note of how Pollard, in 1965, framed empathy with incoming Black students as a parallel to empathy that nurses must show with patients. “It’s nice to connect in that way. It’s nice to remember how great she was.”

Still, the transcript raises painful points. Parsons-Pollard cited not only the self-doubt and lack of support that Pollard had to navigate at MCV – but the 1965 event itself.

“I was angered by the entire exercise. As a faculty member and higher education administrator for over 20 years, I can’t imagine asking a former student who went through what Anne did to come and educate ‘us,’” Parsons-Pollard wrote by email after reading the full transcript. “Those highly educated people knew precisely the impact segregation had on Black people, and scholars were writing about how schools prepare for integration. After all, this interview was seven years after Ruby Bridges went to school in Louisiana. To think that they should ‘interview’ the only Black person to graduate from the program as their one-person survey sample is dehumanizing and manipulative.”

Initial steps on a continuing path

At the time, publicly revealing the clear hurt stemming from Pollard’s treatment was one means of highlighting the scourge of racism. In his book, Peeples wrote that the 1965 faculty session had set a positive tone, including “a discussion of some of the proven principles and practices for successful intergroup work, such as analyzing cultural assumptions in course materials and making time for constructive debriefing sessions after a racially sensitive situation.”

He added that the two Black students who entered the MCV School of Nursing in the following school year did well, “and that some faculty believed that our session had set the tone for this success.”

Reading Pollard’s words today reminds her family of how hard it was – and continues to be – for those who break barriers.

“I pray history will remember her and those like her with the honor, dignity and respect they deserve,” Parsons-Pollard said. “It’s relevant to me because there are people in the world who would have us forget that segregation existed and that it was harmful – not only to those marginalized but to the majority population as well.”

She sees some hope in the fact that Black students now account for 20% of VCU’s nursing program, which also has developed an extensive diversity plan.

“I’d like to think that my alma mater, VCU, is better than it was in the past and will continue to strive toward inclusive excellence,” Parsons-Pollard said. “Charlotte Anne Wynn Pollard was one of many people who moved the institution beyond its history.”

Pollard, who at one point fought breast cancer that was in remission for two decades, later developed lung and brain cancer. She died on Aug. 18, 2001, at age 66, surrounded by friends.

Donald Jr. said his mother was always seeking knowledge – and looking to share it – as shown by her perseverance at MCV and beyond.

“While she may have been the first down the alley,” he said, “she was always trying to bring others with her.”